Recently a friend and I visited Arlington House. I will not retell the history of the Arlington estate in this post but direct you to check out the website.

Side view of Arlington House including the massive front portico. Photo taken by me.

I will retell the experience we had at the site. Upon entering the area immediately around the house, visitors gather on the front portico which has a stunning view overlooking Washington, D.C. The ranger explained a few details of the house’s architecture regarding the brick construction to which stucco was applied and scored to look like marble. He then explained that this was the home of George Washington Parke Custis, the grandson of Martha Dandridge Custis Washington and step-grandson of George Washington. He noted that Custis and his wife, Mary Fitzhugh Custis had only one child to survive to adulthood, Mary Custis. The guide noted that Mary Custis married Robert E. Lee in 1831. He then saw an opportunity to get us into the house and said he could allow 15 into the building and so we progressed forward into the central hall.

The family parlor at Arlington is where Mary Custis married Robert E. Lee in 1831. Photo taken by me.

In the hall we had a ranger who explained that we could look into the Family Parlor, which is where Mary Custis and Robert E. Lee were married. She also explained that the main portion of the house where we were standing was not finished until 1818. The crush of the next group pushed us along while we picked up brochures and some other literature and snapped some photographs of the Family Parlor and Dining Room. We passed through the Hunting Hall and then upstairs.

Upstairs, for an unknown reason to us, a volunteer was engaged in a deep discussion with some visitors about Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1-3, 1863). Perhaps he had been questioned by the visitors about Lee at Gettysburg. Thus I couldn’t fault the volunteer, though, I wished there had been some interpretation about the Custises and Lees at Arlington. As there were a lot of visitors upstairs and more coming, we had to be quick about our looking into the bedrooms. The staff was in the process of repositioning the furnishings in these rooms. Arlington’s furnishings were removed from the house for a few years while a major restoration took place, interrupted in part by the now infamous 2011 earthquake.

The White Parlor at Arlington was not finished until 1855 and the Lees purchased fashionable Rococo Revival furnishings for the space. When we think about the beauty of these furnishings, we must also think about who had to clean and maintain these items. In the Lee household, that task fell in part to the enslaved housekeeper, Selina Gray. Photo taken by me.

Back down the stairs we go and through the White Parlor and then into the Morning Room. It was there (finally) that I didn’t feel pushed along by the force of the people progressing through the house. The ranger in this room explained the art painted by G.W.P. Custis, several of which were exhibited and all of which show George Washington during the Revolution. Additionally, she stated that it was in the office that they believe Lee wrote his letter of resignation from the U.S. Army in 1861. She noted that Mrs. Lee spent a considerable amount of time in this room as her rheumatism decreased her mobility in the 1850s. I questioned her about how many slaves the Custises owned. She responded about the 63 that were at Arlington. I clarified “As I recall, there were over 200 scattered across all the different farms?” She said “Oh yes, that is true. Properties that extended into multiple counties.” She then launched into a discussion about Selina Gray, who was an enslaved domestic servant that was not taken by Mrs. Lee and her children but rather left to guard the Washington and Lee family furnishings in May 1861. The ranger (rightfully) credited Gray’s determination to see the furnishings preserved by the occupying Federal troops during the early months of the Civil War. Then we exited the back of the building.

So I have asked myself some questions:

1. When touring the house did I learn anything about slavery? Not as slavery was practiced by the Custis or Lee families at Arlington or as it was experienced by the 63 people who lived and worked as slaves there.

2. Did I gain any insight on the relationships between slaves and masters? Somewhat through the story of Selina Gray but in that case it was more about the relationship between Gray and the Federal troops.

3. Did I learn anything about the relationships between slaves and other slaves? No.

So we progressed on to two surviving slave quarters for domestic servants in the rear of the Custis-Lee mansion. These two slave quarters are masonry, covered in stucco and composed of three rooms. The south Slave Quarters has an exhibit on slavery and the Freedmen’s Village and a model of the Freedmen’s Village. The village established during the Civil War, was a camp of thousands of slaves who had escaped in search of freedom.

George W. P. Custis painted this horse to represent one of George Washington’s above one of the doors on the north Slave Quarter. Two others depict the American eagle. All of these Americana scenes, ironically painted on a building to house people whom at no level of government were considered American citizens. Photo taken by me.

The panel “Slavery and Emancipation at Arlington” discusses individual enslaved people’s stories, perhaps one of the most interesting to me was Sally Norris, who prepared bodies for burial amongst the enslaved community. Photographs were present of several people as well.

It was also within this panel that you learn some of the names of the people who worked and lived at Arlington. Men like Lawrence and Jim Parks, who were field hands and Eleanor Harris and Ephraim Derricks who were domestic servants.

Interpretive signage is generally short, which makes this one rare with three full paragraphs. Some sentences did raise curiosities which needed further explanation such as “Far from powerless, many slaves possessed significant authority, and sometimes dictated the daily routine at Arlington.” What did the slaves do at Arlington to dictate the daily routine? I think the inclusion of Sally Norris helped illustrate that slaves possessed some specific authority.

The panel highlights manumissions given by George W. P. Custis and the dispersed status of some of those manumitted. Even though the site’s subtitle “the Robert E. Lee Memorial” could lead to a wholly one-sided view of the famed Confederate Army of Northern Virginia commander, this panel did not ignore the reality of the enslaved community’s dislike of Robert E. Lee compared to G.W.P. Custis. In one statement you can see that Wesley and Mary Norris ran away (though the story as printed on the panel does not follow-up what happened with them).

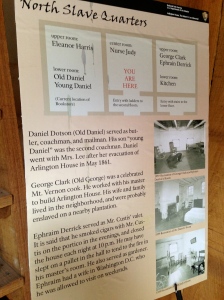

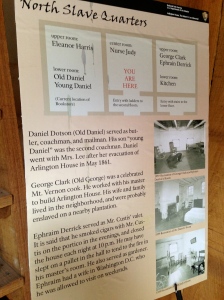

The north Slave Quarter has just recently been vacated of office space and a bookstore and is undergoing rehabilitation to reflect the people who lived in the building. The interpretive panels in this space were some of the best at the site.

This interpretive sign gives you a sense of how this building was used. Notice that Eleanor Harris lived upstairs and she aged considerably in her years as she once was George W. P. Custis’ nurse and then his daughter Mary’s nurse, and later a housekeeper as noted in another sign. Also notice the photographs of the 1959 interpretation of these rooms. Photo taken by me.

In the center room, you see a floor plan of the structure which shows how the spaces were divided. The center room was occupied by Nurse Judy, while the room to the left on the lower floor housed father and son, both named Daniel Dotson. Both were coachmen and Old Daniel Dotson also served as a butler and mailman (presumably someone who took letters to be mailed and picked things up from an unknown location). Perhaps the most surprising element on this sign was the discussion regarding Custis’ manservant and gardener, Ephraim Derrick who reportedly smoked cigars on the portico with Custis at night and then closed up the house at 10PM. The inclusion of the possibility of Derrick sleeping on a pallet on the floor in the hall in order to tend a fire in Custis’ bedroom sends a clear message, however, that Custis did not treat Derrick as an equal.

Also on the same sign was some institutional history. Three photos show how the National Park Service (NPS) interpreted these three rooms in 1959. There was some fairly fine furnishings in these rooms in 1959 which do not accurately reflect how these enslaved people lived in the space. The signs stating “Restoration in Progress” as well as other signs that mention the NPS is embarking on a historic structures report and furnishings plan give great reason to hope that one day we’ll see a more accurate representation of how the domestic servants lived.

While around the north Slave Quarter, we encountered a great ranger, Dean Bryson. My friend and I conversed at length with Dean about the challenges of trying to discuss in any detail anyone (white or black, free or enslaved) when you literally have thousands of people coming through the house daily. But it was also clear that Dean knew and was passionate about Arlington’s plantation history and the NPS’s ownership history. We chatted about those slaves less concerned about the Washington-Custis-Lee family furnishings such as the Bingham family. Dean told us that the Binghams were some of the slaves who reacted negatively to Robert E. Lee’s management of Arlington. Austin Bingham ran off in 1858 into Washington, D.C. where his sister, Caroline and her child were also trying to evade Lee. Fellow blogger Jimmy Price is investigating if their other brother, Lucious may have enlisted in a US Colored Troop regiment late in the Civil War and Dean told us this story as well. We also discussed that while Selina Gray’s determination to save the historical objects associated with George Washington was important, she does present a “loyal slave” narrative. Her image appears frequently throughout these quarters. Dean’s knowledge of the Binghams helps to balance that there were a multitude of feelings within the enslaved community at Arlington. Finally, we discussed the challenges of representing the plantation landscape at large when most of it is now covered by Arlington National Cemetery (not administered by the National Park Service). I am hopeful that Dean may find permanent employment in the agency. We have to have people like him at all our historic sites.

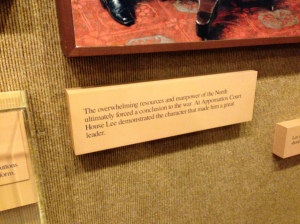

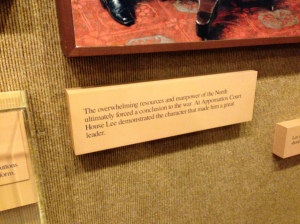

Our final stop was in the Robert E. Lee Museum, housed in a portion of what had been part of a greenhouse. This is the one area of the site that has largely outdated exhibits. However, in the current environment, it will probably remain this way for a while. In a few places the text was difficult to read due to flaking over the years. However, even with the budget challenges, there was a refreshing sign simply typed in a word processing program and printed with your basic inkjet.

This text almost screams of the ragged Confederate, Lost Cause ideology present at many Civil War sites for generations. Like many other memories of Appomattox Court House, this one fails to mention that Lee attempted one last offensive maneuver on the morning of April 9, 1865 before deciding to surrender his army. Photo taken by me.

That sign updated the old exhibit about Robert E. Lee’s resignation from the U.S. Army in 1861. This is based largely on a letter written by Lee and Mary Custis Lee’s daughter also named Mary Custis Lee. The information was discovered by author Elizabeth Brown Pryor (who wrote Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee Through His Private Letters published in 2007). So can exhibits be updated on a shoestring budget? Yes. Should they be? Not really; however, this temporary fix sits in juxtaposition with the exhibit featuring miniature representations of Lee and some of his family at the time. It elicited curiosity from other visitors and helps to illustrate that history isn’t always something that we’ve known since a long time ago. New research and interpretation is on-going in the history community.

This simple piece of paper printed and laminated helps to address new interpretations through historic research. Public historians can really help to spread the word about academic historians’ books and articles as is illustrated here. Photo taken by me.

So I have asked myself the same questions again:

1. When touring the slave quarters and talking with Dean did I learn anything about slavery at Arlington? Yes. I asked about Ephraim and the smoking of cigars with Custis as that still fascinates me. It was apparently recalled by one of the former slaves or one of their children when interviewed in the early 1900s. I also heard about resistance to Robert E. Lee. Through the exhibits in the buildings, I saw what slaves were doing in their tasks on the estate and ways that they were entrepreneurs.

2. Did I gain any insight on the relationships between slaves and masters? Yes, Ephraim clearly had a different relationship with the Custis family than many other slaves. Dean discussed how Selina Gray’s domestic service would have made her acutely aware of what were the “Washington Treasures.” And yet, clearly in the panel in the south Slave Quarter and in conversation with Dean, (the evidence comes from Lee’s letters and memories of the formerly enslaved, see Pryor’s Reading the Man) there was unhappiness over Lee’s management of Arlington so evident in some of the Norrisses escape mentioned in the text and discussed by Dean regarding the Binghams.

3. Did I learn anything about the relationships between slaves and other slaves? Yes. Time and time again in the panels in the north and south quarters. From family relationships with the Daniel Dotsons to the people who were freed and that stayed nearby as at that point they were intertwined in marriage and extended family with the enslaved people at Arlington.

So what can be done to address the challenge of the mass of people who come to Arlington National Cemetery and then enter the Arlington house? I’m not sure. Other than creating a timed ticket system, there will be no other way to control all the people. The NPS has a ticket system to access Independence Hall. The boats to Fort Sumter also operate on a timed ticket system. While it isn’t optimal, this could help improve the time spent in the house for fewer people but with greater interpretive power.

I really did enjoy my visit to Arlington house, even though I continue to maintain that it should be remembered as Arlington House, a memorial to George Washington and then left to Mary Custis Lee and a place of bondage for numerous families from 1802-1861.